di Andrea Romanazzi

After a long journey that led me to attain the rank of Druid within the OBOD, the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids, I have decided to publish, a series of my reflections on Druidism and neo-Druidism. If the former has been studied and explored by various scholars, even within the pages of this Magazine, the latter, neo-Druidism, is less examined. It is a spiritual and/or religious movement based on Celtic culture and Druidic wisdom, which falls within the diverse realm of neo-Paganism, and generally promotes harmony, connection, and respect for the natural.

The Emergence of Neo-Druidism

Modern Druidism was born in the 1700s with the contribution of William Blake and Masonic and Rotarian culture, as well as a renewed interest in the ancient origins of the English people and antiquarian art. Always, megalithic sites like Stonehenge or Avebury had attracted the curiosity of scholars, but it was with the advent of English Romanticism that such constructions began to attract historians who sought to understand their origins and purposes. Many of these, being pre-Roman constructions, associated them, incorrectly, directly with the Celts and their priests. Thus began the association between Druids and Megalithism. The first to associate such sites with Celtic populations was an English antiquary, John Aubrey, in his essay “Templa Druidum,” and later a doctor from Lincolnshire, William Stukeley, who soon defined himself as a “new” Druid, taking the name Chyndonax. It was Stukeley who also defined, actually drawing from the famous 17th-century text “Britannia Antiqua Illustrata” from 1676, the figurative archetype of the Druid, characterized by a hooded cloak, a staff, a short tunic, and a long white beard. Instead, John Toland, an Irish philosopher and writer, founded the first neo-Druidic order, the Ancient Druid Order. An oral tradition suggests that in 1717, at the “Apple Tree Tavern” pub, he gathered the most important representatives of English Masonic circles, in what later became the first official grove called the “Mothergrove,” officially inaugurated in the autumn equinox of 1717 on Primrose Hill, a hill located in the northern part of Regent’s Park, north of London. However, the most important figure for modern Druidism is undoubtedly Edward Williams, who in 1747 gave life to the first Welsh neo-Druidic movement, “Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain,” of which he proclaimed himself an arch-Druid with the name Iolo Morgannwg. Many of the modern Druidic rituals still in existence today, such as the Invocation of Peace, are attributed to him, as is the very symbol of neo-Druidism, the Awen, depicted by three straight lines that radiate within a circle or a series of circles. This marks the beginning of the Druidic revival; the first groves, literally “groves,” and Druidic orders were born, which initially were more akin to para-Masonic societies. We are still far from the neo-Druidism as we know it today. Many of the rituals had Christian and Masonic influences, meaning a religious practice based on the worship of a monotheistic deity. In 1781, the Ancient Order of Druids was founded, known by the abbreviation AOD. Among its members were Gerald Gardner, the founder of Wicca, and Ross Nichols, whom we will discuss shortly. In around 1833, about half of its members separated from the central lodge. This gave rise to the United Ancient Order of Druids, which, by 1846, already had 330 lodges in England and Wales, and also became the first order to spread to America and Australia. However, it was in the 20th century that neo-Druidism took on its more modern image. Ronald Hutton, in his book “The Druids,” writes that Druidism in its current form developed between 1909 and 1912 around the figures of George Watson, MacGregor Reid, Thomas Maughan, and Ross Nichols. In 1909, Reid founded The Druid Order, also known as An Druidh Uileach Braithreachas. The Order, with an initiatory character, is still active today. When Thomas Maughan was elected head in 1964, some senior members, including Ross Nichols, left the grove to establish the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids, better known by the acronym OBOD, of which, as mentioned, I am honored to be a part. While Gardner focused on Wicca, Nichols worked to change Druidic practice and make it more “current.” He introduced the celebrations of the eight seasonal ceremonies and organized teachings into three degrees: Bard, Ovate, and Druid. The Druidic ideas of Ross Nichols were explained in his “The Book of Druidry,” actually a posthumous work. In the 1960s, thanks also to the association of neo-Druidic practice with new eco-environmentalist and hippie movements, the strong natural connection and its interconnection with the shamanic world were rediscovered, as well as the esoteric tradition of the West with the philosophy of the Far East. Modern neo-Druidism thus moved away from the early Druidic revival, which was more tied to a Masonic view of the world and a form of secret society that was becoming increasingly anachronistic and certainly incompatible with an increasingly globalized culture, to embrace a vision of recovering and preserving ancient and indigenous traditions and the search for a sustainable lifestyle, connected to a reconnection with Nature and the Spirits it holds. At the end of the 1970s, former Wiccan Philip Shallcrass, together with Emma Restall Orr, founded the British Druid Order (BDO). The idea was to create a more distinctly “pagan” order, but this collaboration had a short life, and in 2002, Orr left to create The Druid Network, more of a network structure aimed at a global community and a view of the Druid tradition focused on ethics, ecology, and spirituality. Coming to the present day, between 1985 and 1988, Tim Sebastion founded the Secular Order of Druids (SOD), defining himself as a “Modern Druid.” The organization, also known as the Council of British Druid Orders, was mainly created to defend access to Stonehenge for the performance of neo-Druidic rituals, but its structure and training were more geared towards a single and contemporary Druidism. Despite the name, “Secular,” this order today defines itself as animist and polytheist. Another organization of great importance, the most numerous of all, is the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD), founded in 1964 by Ross Nichols. It also offers correspondence courses through lessons known as “gwersi.”

Female and Druidism

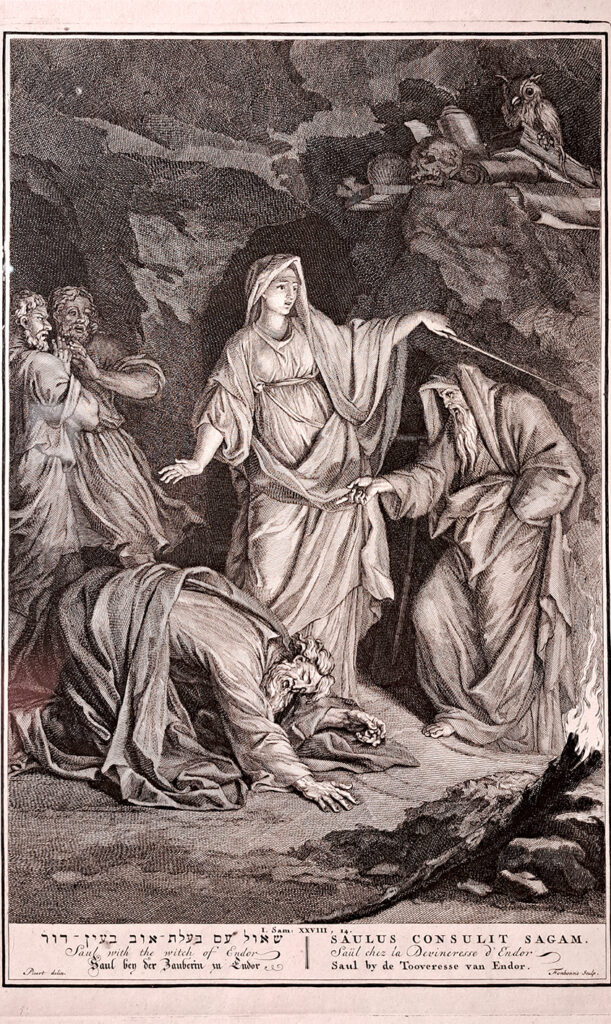

It has its own liturgy, introduced by Nichols himself and subsequently revisited, and its own form of seasonal celebrations. The order also focuses heavily on the relationship with the spirits of Nature, which it defines as real spiritual entities. Equally important, especially within the Italian context, is the Cultural Association “Druidismo e Antica Religione Celtica” (DARC), founded by the ultra-seventy Stefano Mari, which as of 2021 already has over fifty members throughout Italy. DARC is a cultural association with a strong spiritual character, which provides a point of reference for all those who wish to deepen and cultivate their knowledge of Druidism and ancient Celtic religion. The association, through a private forum and national and international conferences, allows members to meet and confront each other, sharing knowledge and opinions. As with other religions and other spiritual paths, in recent decades, the female element has also found space within neo-Druidic practice. In its origins, neo-Druidism was predominantly male due to the strong influence of Masonic and Rotarian lodges, which were typically male spaces. Only thanks to the spread of the English environmentalist and pacifist counterculture and the rise of feminism in the late 19th century did the image of the female figure enter the Druidic movement, even if initially in an almost symbolic way. From an iconographic point of view, the romantic English vision introduced the female figure into the neo-Druidic movement, at least in art. Paintings and illustrations depicted female Druids as well, and by the 1970s, it was unthinkable not to consider women within the movement, especially given the increasingly eco-pagan and spiritually-inclined culture. However, the historical evidence of the presence of women as Druidesses is not that obvious. In Irish literature, for example, we find references to female Druidic figures, such as Scathach, who is explicitly called “flaith,” or prophetess. The Roman historian Tacitus, in his “Agricola,” speaks of the presence of Druidesses during the conquest of Anglesey. The Greek geographer Strabo, in his “Geography,” speaks of a group of priestess-women called Samnitae. Moreover, the roles of women among the Druids are not entirely clear. We know that they held positions of religious and high standing, as already reported by Diodorus Siculus in his “Library of History,” where he speaks of the role of women among the Celts, or even by Posidonius, a Stoic philosopher, who in his work “Histories” states that women practiced divination and were capable of understanding and interpreting the signs sent by the gods, and that they also acted as judges and mediators. The role of the women we know about seems, in fact, to be related to divination and oracles, as well as mastery of natural elements. There are also many examples of women who played an important role in Celtic society, for example, Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, who, during the revolt against the Roman occupier, was able to rally numerous tribes and obtain considerable successes. On the other hand, their role seems to have had a slight difference compared to their male counterparts, which is difficult to define with certainty. For example, according to the sources, they did not cut the mistletoe with a golden sickle, while their male counterparts did.

the cult of trees in Druidism

As mentioned earlier, the connection between neo-druidism and the natural world is already present in the vocabulary itself. The term “grove,” meaning a small forest, denotes a group of practitioners, consisting of few or more members, who share rites of passage, initiations, celebrations, and much more. We have then seen how the most representative image of the druid has always been one that sees him in an oak forest, a symbol of resistance, purity, and constancy in teaching or gathering mistletoe. In the 19th century, in all druidic representations, acorns and oak leaves are found adorning engravings, medals of druidic orders, etc. One of the most well-known depictions is, for example, “Druid in an oakgrove near Stonehenge with a sickle and mistletoe” by Francis Grose, dated 1772-87.

But is the relationship between the Druid and the oak really so privileged, and why? If it were a mistake? The link between the Druid and the Oak is certainly related to etymology. Pliny, in Naturalis Historia, connects the term to the Greek root of the word oak, “dryas,” and the Indo-European suffix “wid,” meaning knowledge, thus those who know through the oak.

“The Druids considered nothing more sacred than mistletoe and the tree on which it grows, as long as it is an oak. They already choose oak groves as sacred, and they do not perform any religious rite unless they have branches of this tree (…). They consider everything that grows on oak trees as sent from heaven, a sign that the tree has been chosen by the deity itself. Moreover, oak mistletoe is very rare to find, and when discovered, it is collected with great devotion: first on the sixth day of the moon (which marks the beginning of the month and the year and the century for them, every thirty years) because on that day the moon already has enough strength and is not half. The name they gave to mistletoe means ‘that which heals everything.’ After preparing the sacrifice and banquet according to the ritual at the foot of the tree, they bring two white bulls, to whose horns branches of mistletoe are tied for the first time. The priest, dressed in white, climbs the tree, cuts the mistletoe with a golden sickle, and gathers it in a white cloth. Then they sacrifice the victims, praying to the god to make the gift (the mistletoe) favorable to those to whom it is destined. They believe that mistletoe, taken as a potion, gives the ability to reproduce to any sterile animal and is a remedy against all poisons.”

However, perhaps that etymology is not the most accurate explanation. Jan de Vries, in La Religion des Celtes, expresses his skepticism about the connection between druids and the tree; much more likely, the term “druid” could derive from “dru-vid,” meaning strength, wisdom, or, according to Le Roux and Guyonvarch, from “dru-wid,” meaning wise man. So why does Pliny connect druids to oaks? Well, this has always been a sacred tree in the Mediterranean tradition. Acorns, probably, were the first fruit to provide “flour” to humans for the preparation of bread. The most important among the Mediterranean gods, Jupiter, was connected to the oak cult. In classical times, festivals in honor of Zeus Dodoneus were held in “forests of oaks,” at the feet of which pieces of meat were placed, which then became food for birds that were used for divination. Virgil narrates that on the Capitoline Hill, the first temple dedicated to Romulus was built near a sacred oak. During the Capitoline festivities related to the god, the winner was adorned with a crown of oak leaves. This consecration must have even deeper roots; according to Frazer, the kings of Alba had to wear oak crowns, and that population was also called “men of oak,” probably because of the forests they inhabited. If not the oak, then, what is the sacred druidic tree? It could be the Pine, after all, Merlin himself achieves the power of Knowledge, Prophecy, Metamorphosis, and Language only after climbing the sacred Pine of Barenton: the cosmic tree. According to Robert Graves, however, the true sacred plant of the druids was the Birch. In The White Goddess, the scholar highlights how this tree opens the Celtic year. It is connected to solar rebirth, and therefore, we find it in rituals related to the Winter Solstice. Its sacredness is also manifested on Candlemas Day and, in Welsh tradition, at Beltane, as this tree provides the trunk for the Maypole. The story in the Book of Ballymote says that Ogma, son of Elathon, manuscript dating back to 600 A.D., claims that Ogma engraved the first Oghams on birch wood. Other writers question the primacy of the Birch in favor of the Apple tree, the missing hero not for strength and courage but for “language.” In the Vita Merlini poem, it is narrated that the famous druid used to teach under this tree. In Breton mythology, before prophesying, one had to eat an apple, a fruit that allowed connecting the worlds. In the Yr Afallennau and Yr Oianau compositions, the madness of Mago Merlin, who, in a forest, spoke with an apple tree, is described. Madness or Vision? The Apple is the food that comes from the Otherworld, as demonstrated by the adventure of Condle, son of King Conn, who receives an apple from the Lady of the Otherworld that nourishes him without ever being consumed. The apple tree is, therefore, the tree of the Otherworld that grows in Avalon, the mythical world where heroes rest. Finally, let’s not forget the Yew, as highlighted by Chetan and Brueton in the essay The Sacred Yew. Rather than a connection between the Druid and the Oak, it might be more accurate, in my opinion, to emphasize the strong relationship between the Druid, the neo-druid, and the cult of the Trees, the druidic temples where they could perform the necessary rituals for the community and now transformed into modern “groves,” metaphorical woods where neo-druids gather. Although many neo-druids today choose to work alone, there are numerous associative entities that can offer the opportunity to meet for festival celebrations, rites of passage, rituals, teachings, as well as a way to meet new people, share ideas, and create experiences. In Italy, there are several groves and neo-druidic lodges. The link https://druidry.org/get-involved/groups-groves/groves/groves-in-europe lists those affiliated with OBOD, while the link https://www.druidry.co.uk/groves/, after a brief free registration, provides information about BDO groves… (Continues)

Lascia un commento