di Andrea Romanazzi

In the northern lands, where rain-laden winds sweep the hills and grass bends toward the sea, the night of October 31 has never been just a prelude to All Saints’ Day or an excuse for masquerades. It marks the threshold of winter — the moment when the visible world and the invisible brush against one another.

Long before Halloween became a global spectacle, it was, throughout Celtic Europe, a night of ancient rites, bonfires, and divinations. In Ireland it was Samhain, in the Isle of Man Hop Tu Naa, in Wales Nos Galan Gaeaf, and in the Scottish Highlands simply the Winter Eve.

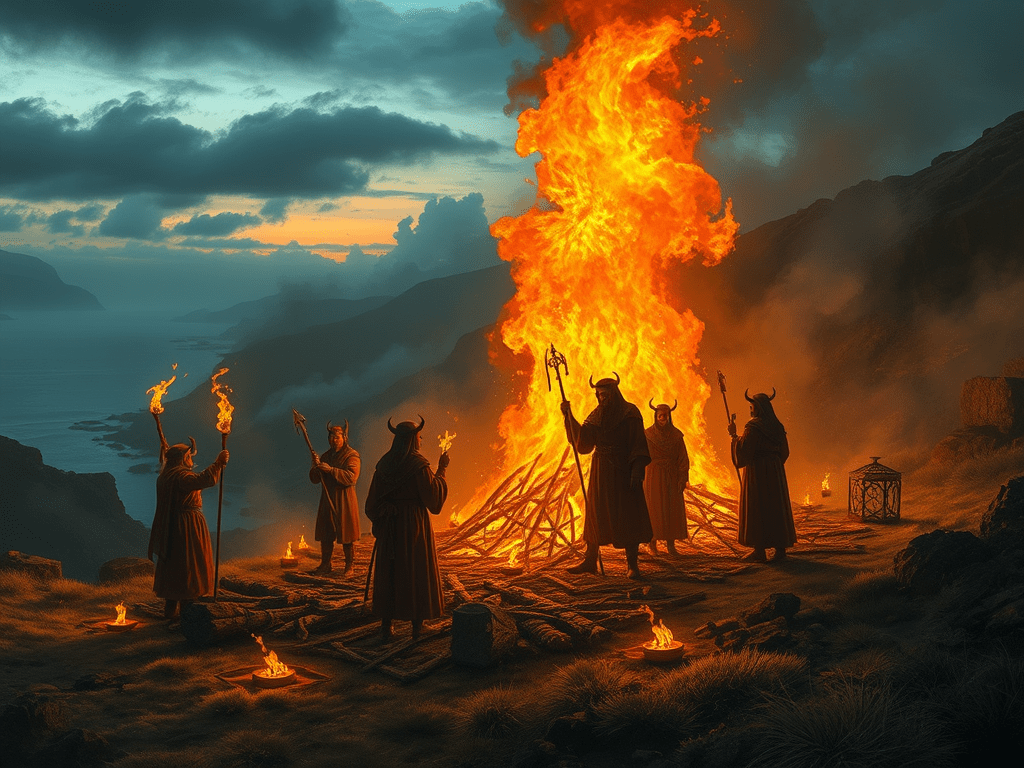

Fires on the Horizon: The Night of the Threshold

In the Scottish regions of Sutherland and Caithness, as the sun set on October 31, hillsides blazed with bonfires. The flames served both as protection against evil spirits and as a bridge to the unseen. Fire was thought to burn away harmful influences, while its smoke and ashes held purifying power.

Until the nineteenth century, torches were carried around the fields following the course of the sun, in gestures at once apotropaic and propitiatory. When the fires died down, villagers gathered the ashes in a circle and placed a stone for each person present. If, at dawn, one of the stones had been displaced or cracked, it foretold that its owner would die within the year.

It was a stark, silent divination — a dialogue between fate, fear, and fire.

The Maritime Samhain of the Hebrides

In the northern Hebrides, Samhain carried the scent of the sea. On the island of Lewis, in the village of Bragar, people brewed barley ale as an offering to Shony, the sea-god, so that he might grant a plentiful harvest of seaweed — vital fertilizer for their fields. The beer was poured into the waves with prayers and invocations, a delicate transaction between human toil and the vast, capricious ocean.

The gesture, uniting sun, water, and fermentation, embodied the rural cosmology of giving back to nature what life had lent.

Nos Galan Gaeaf: Apples, Flames, and Omens

In Wales, the “Eve of Winter” was also the Night of Apples and Candles. People kindled gorse fires on the hills, roasted apples and potatoes, sang, and danced. Young men leapt through the flames to ensure health and good fortune, repeating, perhaps unconsciously, an ancient solar rite of renewal.

Here too the divination of stones survived: each participant cast a marked stone into the fire and examined it at dawn. An intact stone promised protection; a blackened or moved one foretold misfortune. Fire was not merely warmth that night — it was language.

Hop Tu Naa: The Children’s Songs of the Isle of Man

On the Isle of Man, the seasonal boundary was called Savin, the Celtic New Year. Children wandered through the villages carrying lanterns carved from turnips, singing ritual songs in exchange for small gifts. The celebration, known as Hop Tu Naa — literally “this is the night” — retained the spirit of the ancient magical quest.

Needles of steel were sewn into collars to ward off spirits, and divinations about the weather or coming marriages were common. Over time, these practices drifted toward Christmas and New Year, preserving their essence of renewal and protection.

The island’s children, singing door to door, anticipated by centuries the modern trick or treat — a playful echo of an older pact between generosity and the unseen.

Cailleach Bheur, the Blue-Faced Hag of Winter

In Scottish lore, Samhain marks the awakening of Cailleach Bheur, the goddess of winter — an ancient personification of cold and the sleeping earth. Described as an old woman with a blue face and hair of frost, she begins her reign on this night.

Families lit their hearths not only for warmth but in quiet acknowledgment of her dominion. Within her figure intertwined death and renewal, decay and protection: she was both destroyer and caretaker of the natural world through its long slumber.

The Breton Turnips and the Light of the Dead

Across the Channel in Brittany, the night of October 31 still carried Samhain’s breath, though tinged with Christian customs. Food was left outside for returning souls, and children carved faces into turnips to make the first lanterns of the dead.

Eyes, nose, and mouth were hollowed out, and a candle placed inside — a humble globe of earth glowing with spirit. When Irish emigrants brought the tradition to America in the nineteenth century, they replaced the scarce turnip with the abundant pumpkin. Thus the modern symbol of Halloween was born.

Masks, Mischief, and Sacred Chaos

In the Highlands, Halloween was also a night of mischief. Youngsters swapped gates, moved carts, and dressed in grotesque disguises so that spirits would not recognize them. The costume was not mere amusement but a shield: anonymity as protection.

This ritualized disorder carried sacred weight. To overturn the rules was to honor the renewing force of chaos, reminding the community that creation begins in dissolution. Those who refused the joke risked worse pranks the following year — a warning that ritual chaos must be accepted, not resisted.

Purification and Renewal

From the Hebrides to Wales, a single thread binds all these customs: rebirth through fire. Villagers danced in circles following the sun’s path, leapt through flames to cross symbolically through death, and scattered ashes on their fields to feed the coming spring.

It was not superstition but an ecological wisdom. Fire consumes, yet it purifies; it destroys, yet promises. In October’s darkness, the bonfire assured humanity that the sun would rise again — that every ending is only a threshold to renewal.

From Celtic Threshold to Global Celebration

Today Halloween sparkles with masks, lights, and sweets, yet behind its brightness breathes the echo of ancient fires. In the Hebrides, people still tell tales of Shony; on the Isle of Man, children still sing Hop Tu Naa; and in Wales the scent of roasted apples still marks Nos Galan Gaeaf.

Everything changes, yet the meaning endures: to cross the darkness in order to return to the light.

In its deepest sense, Halloween does not celebrate the macabre but the courage to face the threshold. It is the night when the world of the living grows permeable to that of the dead — and, in recognizing our own fragility, we renew our pact with life.

Lascia un commento