di Andrea Romanazzi

Every year, on the first of October, we prepare to be bombarded by advertisements, magazines, and networks talking about Halloween, the November carnival, a true celebration of the consumeristic Western world. For many, this event is foreign to our Italian culture, a clear example of the effects of globalization and the assimilation of customs from the Anglo-Saxon world. In reality, hidden behind masks and sparkling shop windows, ancient memories of traditions that were never entirely lost still emerge, deeply ingrained in the popular folklore that defines our nation. It is by following the clues hidden in the folds of time that we arrive at a very ancient cult, the cult of Death and Natural Regeneration, the queen of this mystical night where even today the veil of reminiscence is so light that it allows us to see through it.

According to the McBeain Gaelic Language Dictionary, Samhain (pronounced “sow-in”), perhaps the most important of Celtic festivals, is derived from “samhuinn,” meaning “summer’s End,” signifying the end of summer and the beginning of the winter season. In reality, the celebrations didn’t last just one day but began a week before and concluded a week after. It’s much more likely that the most important day of the festivities wasn’t the first of November but the 11th, coinciding with what is now called St. Martin’s summer. Later, in Anglo-Saxon countries, Samhain transformed into All Hallow’s Eve, or Halloween, where “Eve” stands for “evening” or Halloween.

Hence the connection of Samhain as a festival of the dead. But in reality, it’s not a celebration associated with the deceased; quite the opposite, it’s linked to life, to the great goddess who dies to be reborn. The concept of death and resurrection has always permeated human beliefs and myths; in the Greek world, for example, it is well described by the story of Demeter and Persephone. The legend goes that one day, Persephone, Demeter’s beautiful daughter, while picking flowers with her friends, wandered into the woods. Hades, the god of the underworld, deeply in love with the girl, decided to kidnap her with Zeus’ consent. When the Mother Goddess noticed her daughter’s disappearance, she began to search for her. Seeing her attempts in vain, she decided that until her daughter was returned, the earth would not produce its fruits anymore. Zeus ordered Hades to release the girl, but using a trick, he forced her to return to his realm every six months. Demeter, furious, decided that during the time Persephone was in the realm of the dead, winter would come, and the earth wouldn’t yield its magnificent fruits—a metaphorical death awaiting rebirth.

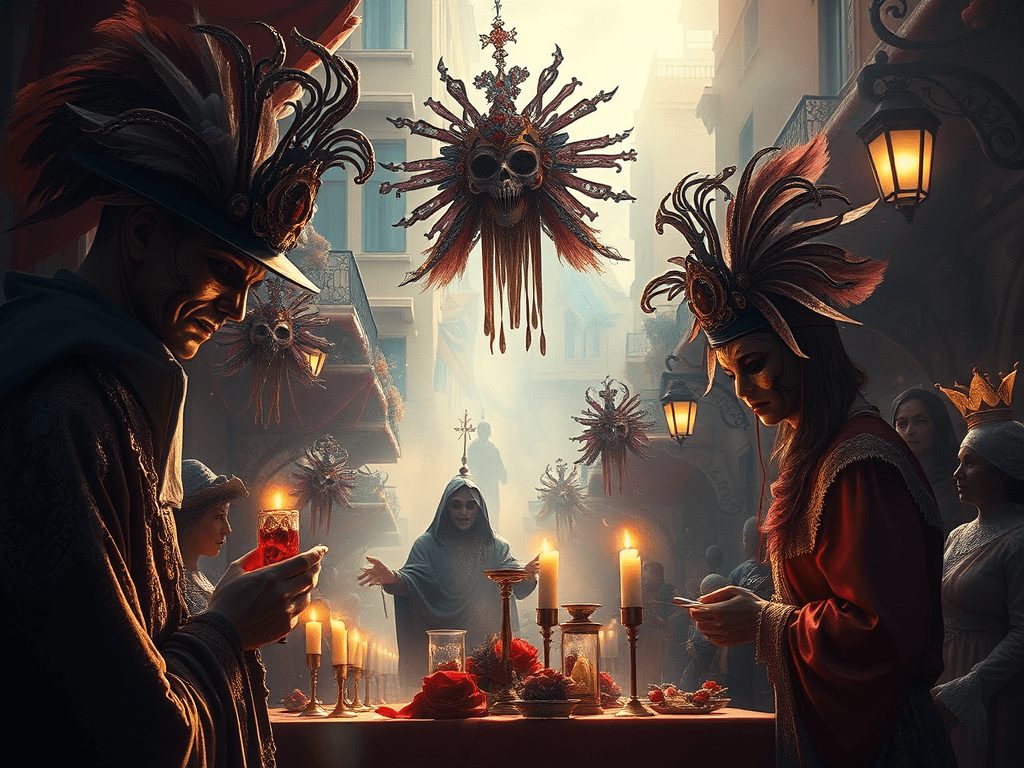

In this perspective, Halloween takes on a new meaning. It becomes the day when the veil between the world of the living and the supernatural becomes very thin, thin enough to easily pierce. Thus, the idea emerged that the souls of the dead could more easily reach and visit their still-living loved ones on this day. From this belief comes the custom of leaving fruits or milk at doorsteps so that the spirits, during their visits, could refresh themselves. Also, torches and lanterns were lit to signal the way and facilitate their return.

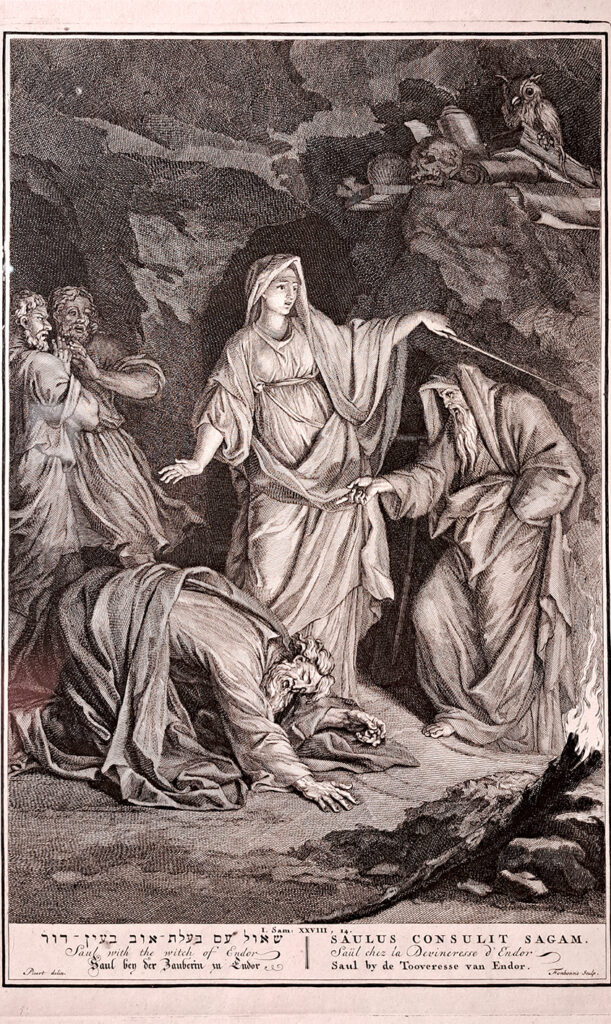

With the advent of Christianity, the Church tried to appropriate this festivity too deeply rooted in popular culture to be eradicated. In the 8th century, Pope Gregory II introduced the Feast of All Saints, and later in 988, Odilo, the abbot of Cluny, established All Souls’ Day. The fairy figures and spirits from Celtic tradition, symbols of an afterlife of death and regeneration, were demonized. The same women whose role in fertility rituals was fundamental were transformed into witches, and the “joyful” bonfires were translated into witch burnings. Even lanterns and guiding lights suffered a similar fate. Originally meant to guide one’s deceased back home, they became “witch-scarer lanterns” with an entirely different purpose.

One of the interesting traditions still observed on Halloween is going door-to-door in costume. While this custom is typical in Anglo-Saxon cultures, it, in a different manner, fits into the interpretation of the festival. In many Celtic lands, these small processions were led by the “cenmad y meirew,” the “ambassador of the dead,” who requested donations of ritual food meant for offerings to the deceased. One of the English terms for the fires lit on this occasion is “bonfires,” meaning “bones fires,” in a tradition quite similar to the ones we’ll explore in Italy.

As we have previously examined in nearly all mythologies, in close symbiosis with the disappearance and natural rebirth, it is the male deity that undergoes a cycle of death and resurrection that has always been associated with the sun. Among natural phenomena, there’s none quite like the death and resurrection that closely mirrors the disappearance and reappearance of vegetation: the natural cycle of fields, with their sowing, growth, and death. It’s the idea of the death of “Dema,” as described by Jensen, the mythical being through which agricultural peoples received the gift of essential plants for their lives. The often violent end of Dema could also be related to the “destruction” by humans of the products of the fields, cut down, threshed, and then reduced to dust. In all primitive-popular cultures, the deity is seen and conceived as immanent; it permeates everything in the wild, in a strongly animistic view. The death of the plant thus becomes the death of the deity, with a series of rituals aimed at regenerating it. It is in these ancient rituals that we find the prolegomena of the mourning ritual, from which Italian traditions for the night of All Saints draw heavily.

The sacred festival to propitiate the rebirth of nature as it heads into its hibernation intertwines, however, with what we could call Fear of the Dead or Necrophobia. It is with the transition from nomadism to agriculture and settled activities, and thus with the burial of the deceased near settlements, that necrophobia [necros=dead and phobos=fear] is born, and thus the rituals meant to defeat it. According to the primitive mindset, the dead, before reaching their homeland in the afterlife, undergoes a sort of intermediate passage, the overcoming of which and the subsequent attainment of that definitive peace also greatly depends on the funeral rituals performed for them by the living.

In Homer, the dead lacking a burial become restless and return to torment humans until they are buried or burned on the pyre. Plato argued that if the soul remained tainted and impure, it could not enter Hades and thus “it rolls among the grave monuments and tombs, around which it is well known that shadowy specters of souls have been seen.”

Thus, actual ritual formulas were born to keep the deceased at bay, from which, albeit with different meanings, Halloween traditions would draw extensively. In this context, we won’t delve into the meaning of the “Funeral Lamentation,” a ritual practice in the process of dissolution or practically already dissolved, of which only vague accounts from the elderly women of southern Italy remain. This practice could be reinterpreted within the context of folk songs during the harvesting operation, as described by Moret in the case of the Egyptian maneros, the Phoenician linos, and the Lityerses, the typical song of Greek harvesters…

n ancient times, offerings of bread were often made on graves; Greeks and Romans commemorated their dead with votive offerings of food and wine on graves (M. Caligiuri, 2001) to appease the souls.

Babylonians and Assyrians buried pots of honey. The use of real food in tombs is demonstrated by various texts such as Michel Raufft’s “De Masticatione Mortuorum in Tumulis” and Philip Rohr’s “Dissertatio Historico-Philosophica de Masticatione Mortorum.” These texts described how the deceased, lacking adequate food supplies, would start to feed by chewing their shroud and their own flesh. Cannibalism also became a way to ensure the second death for the deceased; the stomach became their final resting place. From this interpretation, several Italian popular expressions like “bere i morti” (drinking the dead) or “mangiare i morti” (eating the dead) (E. De Martino, 1959) and the custom of the funeral banquet might have originated. This could be the sense behind the customs we will examine later, where in many regions of the Peninsula, strange bone-shaped sweets are prepared, called “ossa dei morti” (bones of the dead) (A. Romanazzi, 2003), which are then given to children, almost echoing the theme of necrophagy. For instance, in Morcone, Campania, legumes, pears, figs, and granone were distributed as food offerings, with the cry, “cicciotti per le anime dei morti” (little sweets for the souls of the dead). In Sant’Andrea in Conza, long before the global event of Halloween, people used to go around with large hollowed pumpkins shaped like skulls illuminated from inside with “scamurzi,” small leftover candles. The same tradition was followed in Somma Vesuviana, where these “creations” were called “cape ‘e muorte.” Similar examples can be found throughout the Italian peninsula.

Even the typical “pro anima” bread from the Campania region would serve a similar function. The food is often offered during the night vigil, at the entrance of the cemetery or the house of mourning. In some villages in the province of Bari, it was prepared directly on the coffin or graves. In this disturbing ritual of preparation, we find a mitigated form of necrophagy. Eating the bread prepared on the deceased or that has come into contact with them is nothing but nourishing oneself with the deceased. The choice of bread as a ritual food, besides being the typical food of the deceased, is also related to a regenerative view of it, in close symbiosis with death and the regeneration of wheat or cereals in general, of which it is made.

Traditions related to sex are also interesting. Death brought a form of libido deficients, that attanassamento (E. De Martino, 1959), a term used in the Lucanian area, which could not and should not remain. The idea of an increase in libido after death has a dual purpose: the reaffirmation of life through mating but also a way to astound the dead so that they are aware of the great life force opposed to them. After all, obscene display is a way to manifest the energy of the living. Freud states that whoever utters an obscenity launches an attack, equivalent to a sexual assault, eliciting a reaction in the listener similar to what would have been generated by a real aggression. This aggressive act is made against the deceased in this case. Subsequently, from sexual acts and obscenity, the transition is made to laughter, a milder form of the same. Hence the tradition, still practiced today, of telling obscene or sexually themed narratives during funeral vigils that generate hilarity. This is evidenced by numerous popular sayings like “il morto non può uscire senza il riso” (the dead cannot leave without laughter) or “non vi è morto senza riso” (there is no dead without laughter) (A. Di Nola, 2003). In ancient times, there were also funeral dances and forms of hilarity, and the dances that later led to the medieval tradition known as the “Dance of Death,” depicted in many churches and cemeteries, originated. It’s the theme of death, played on the flute, taking the dead away, later interpreted with the idea of the democracy of the Black Lady. In reality, death replaces the pagan flutist who led the funeral procession and later transformed into a “playful dance” around the coffin (A. De Gubernatis, 1869), which might be the archetype of the “trick or treat” processions.

A clue indicating the atavistic origins of the search for libido can be found in the myth of the rape of Proserpina, as described earlier, where Iambe, a servant of King Celeus where Demeter was staying, tries to make her goddess laugh by engaging in an obscene performance. A similar theme is found in the myth of Baubo, who, in order to make Demeter drink the ciceone, a typical mourning drink, flaunts her genitals, generating laughter and thus overcoming Demeter’s lack of appetite (A. Di Nola, 2003). Obscene elements were present in many death cults. In Egypt, mourners often bared their breasts (E. De Martino, 1959), both as a display and as a new symbol of rebirth, as the breast is associated with breast milk and therefore new life. This practice remained intact until the last century; in the Lucanian lament, we find the ostentatio of the mother to her child in remembrance of the milk given and the one lost (E. De Martino, 1959). There were also many traditions of erotic and sexual games during funeral vigils. In Sardinia, there is even a specific figure tasked with eliciting laughter, called the Buffona (F. De Rosa, 1899), while sexual games, such as the game of the Flea, are reported by De Martino in many Lucanian villages.

Lascia un commento