di Andrea Romanazzi

The path of Neo-Druidism is not a monolithic religion, nor a closed system of doctrines. Rather, it is a constellation of spiritual paths that share a common symbolic root: the search for harmony between human beings and the living forces of nature.

Over the centuries, the figure of the Druid—priest, judge, sage, and poet of ancient Celtic societies—has been the subject of continuous reinterpretations, giving rise, in the modern era, to a mosaic of forms that reflect diverse sensibilities and needs. Today, Druidism manifests itself in multiple currents, from the most philological to the most spiritual, from historical reconstructions to intimate and individual expressions. This plurality does not represent dispersion, but a process of adaptation: like a tree growing in different directions while maintaining common roots.

Among the main paths of modern Druidy we can recognize:

- Reconstructionist Druidism, which aims to recreate with historical rigor the cults and practices of the ancient Celts, based on linguistic, archaeological and mythological research.

- Revival Druidism, born from the Romantic nineteenth century and oriented towards a spirituality inspired but not tied to ancient sources, more open to symbolism, poetry and creativity.

- Evolutionary Druidism, which tends towards a holistic vision of the world and the integration of multiple pre-Christian traditions in a contemporary synthesis.

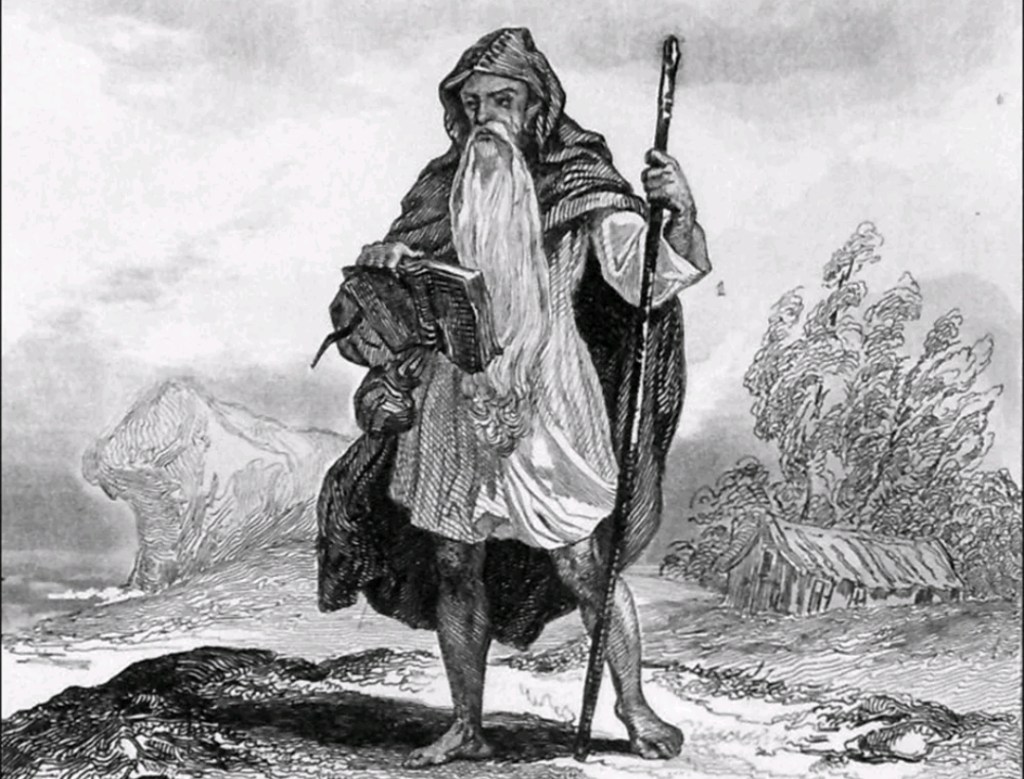

The Hedge Druid – The Lonely Path of the Border

Alongside the collective currents of contemporary Druidry—reconstructionist, revivalist, evolutionist—there exists another, more silent and intimate path, which distances itself from orders, liturgies, and formal ritual structures.

It is a path that does not found temples, does not proclaim doctrines and knows no hierarchies. It is the path of theHedge DruidtheHedge Druid, as the British writer and priestess first defined it in the 1990sEmma Restall Orr.

It was she, among the most influential figures of contemporary Druidism, who brought this archaic term back into use —hedgein the sense of “hedge, limit, boundary” — to describe that form of solitary and intuitive Druidism that arises from a direct relationship with the land and the spirits of the place. The concept later spread to the Anglo-Saxon world thanks to his bookLiving with Honourand at the conferences of theBritish Druid Orderand of theOrder of Bards, Ovates and Druids, becoming a point of reference for those seeking a spirituality free from structures, but rooted in the natural sacred.

Although I belong to several Druid orders and networks, and I celebrate the seasons with friends and fellow travelers, for me Druidism is primarily a solitary journey. Solitude, in the Druidic sense, is not isolation: it is sacred space, fertile silence, a condition in which the voice of nature can be heard without mediation. It is in this stillness—in the breath of the wind, in the changing seasons, in the invisible rustling of leaves—that Druidic knowledge reveals itself not as doctrine, but asliving relationship.

The Hedge Druid, the Hedge Druid, symbolically inhabits that fragile and powerful line that separates and unites the human and wild worlds.

The termhedgeIt holds a dual function: it delimits and connects. It is a boundary and a bridge, a barrier and a threshold. Crossing it means performing an initiatory act: leaving the known to encounter otherness. For this reason, the Hedge Druid is, in a psychological sense, one whotravel between worlds.

In the ancient rural landscape, the hedge marked the boundary of the village: on one side, the community’s territory, orderly and known; on the other, the domain of the forest, of the unknown, of mystery.

It is a border not only physical but ontological: beyond that line lived spirits, minor divinities, presences that escaped human laws.

Whoever chooses to live spiritually on this threshold accepts to dialogue with both worlds, to beinterpreter between reason and instinct, between the light of knowledge and the shadow of intuition. The Hedge Druid, however,puts experience at the center.

Its altar can be a boulder, a leaf, a cup of rain collected in the morning, offering water to a flower, thanking the tree for its shade, healing a wounded animal, leaving a seed in the earth after the harvest—these are simple acts, but in them is manifested the same sacredness that a collective rite celebrates in symbolic form.

Every daily gesture becomes a ritual if performed with awareness: sweeping the doorstep, lighting a candle, listening to the call of a blackbird, observing the movement of the sun through the branches. The spirituality of the hedge is made ofminimal gestures and radical attention.

It seeks not ceremonial power, but the depth of connection. The act of walking barefoot on the ground, of collecting rainwater, of respecting the animals of the forest are not romantic escapes from modernity, but forms of cultural resistance. In their silence, a philosophy of interdependence asserts itself: there is no “outside” or “other”—everything that lives breathes in the same circle.

No authority, no mandatory doctrine: only the direct encounter with the natural world and the certainty that the sacred resides in every fragment of reality. The Hedge Druid does not separate magic from life: he lives magic asembodied attention, a way of inhabiting the world with reverence.

In his actions we recognize an ecological tension that goes beyond the conservation of nature.

It is not a question of defending an external “environment”, but ofrediscovering the human as part of the natural cycleServing the Earth, for the Hedge Druid, is both a religious and political act: it is the defense of life in its entirety, the awareness that every gesture has resonance.

The Lonely Druid Paradox: Freedom Without Certificate

If today the path of the Hedge Druid appears marginal, misunderstood, or even viewed with suspicion, this is less due to its solitary nature than to the cultural context in which it manifests itself. We live in a society in which every form of knowledge, to be recognized, must becertified, certified, made visible through a title, membership or acronym.

Knowledge is no longer an experience, but a document. And spirituality, by extension, often finds itself trapped within the same framework. This tendency is clearly reflected in the contemporary Druid world. Many define themselves as “druids of an order,” “initiates of the circle,” or “members of,” as if the value of their path derived from belonging to a recognized structure. These orders play an important role in education and community, but at the same time they risk—unwittingly—generating a model of institutional spirituality, where personal experience is measured through form, rather than awareness.

The recognition society

Modern humans are no longer satisfied withknow: wants to be seen while knowing.

What once sufficed to be lived in silence—an intuition, a vision, an inner connection—today seems to require public validation. It is the logic ofrecognition society, in which every experience must take the form of a title, a certificate, a qualification.

In the academic world, this attitude builds a resume; in the spiritual world, it generates affiliations. The Hedge Druid, however, disrupts this dynamic. This is why the mystical society struggles to understand it. Where there is no certification, improvisation is suspected. Where there is no authority, anarchy is feared. Yet, authentic spirituality has always been anarchic, in the etymological sense of the term:without external principle, rooted in one’s inner source.

In the silence of the forest the Hedge Druid has no need to show himself, to justify his belonging or to distinguish himself with external symbols. “It is acondition of beingThe Hedge Druid does not belong, but participates. When the need for recognition is removed, the naked experience of the sacred remains. And there, at the point where no order or title can intervene, the true apprenticeship begins.

Lascia un commento