Di Andrea Romanazzi

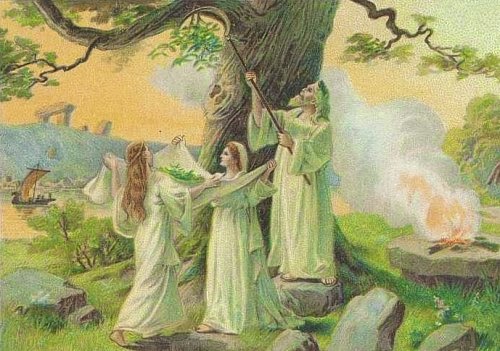

Since I approached druidism I have been told that the most representative image of the druid has always been the one that sees him in an oak forest, a symbol of resistance, purity and constancy in teaching or in collecting mistletoe. In the nineteenth century in all druidic representations we find acorns and oak leaves to decorate engravings, medals of druidic orders etc …

One of the best known representations is, for example, “Druid in an oakgrovenear Stonehenge with a sickle and mistletoe” by Francis Grose, dated 1772-87. But is the relationship between the Druid and the Oak really so privileged and why? What if it was a mistake from the past? An insight to reflect on some of our certainties.

Tree worship has always been present in ancient cultures. Studying the religions of the past one always comes across a cult of the tree, often nicknamed “cosmic” among its branches the known worlds develop, as in the case of Yggdrasill, just to give an example, or because they descended from it for the first time the gods, as for the Ceiba of the South American cults. I have explored these themes in my numerous essays such as “Witchcraft in Italy”, “The Shaman’s Exchange” or “Guide to Afro-Amerindian Shamanism” to which I refer the most curious. However, this study aims to focus attention on sacred trees in the Druidic tradition, a job I did during my journey in the Ovate degree.

“… The oak that moves nimbly, heaven and earth tremble before her, sturdy guardian of the gate against the enemy is her name in every land…”

The link between the Druid and the Oak is certainly linked to etymology. Pliny, in the NaturalisHistoria, connects the term to the Greek root of the word oak, drys, and from the Indo-European suffix owid, or to know, therefore those who know through the oak. Lucan, in his Pharsalia, speaks of the sacredness of oak woods for the Druids.

Perhaps, however, the etymological one is not the most correct explanation. Jan de Vries, in La Religiones des Celtes, expresses his skepticism about the connection between druids and the tree, much more likely the term druid could derive from dru-vid, i.e. strength, wisdom, or, according to Le Roux and Guyonvarchda dru-wid, or wise man.

So why does Pliny connect druids with oaks? Well this has always been a sacred tree in the Mediterranean tradition. Acorns were probably the first fruit to supply the “flour” to men for the preparation of perhaps the first bread. The most important of the Mediterranean gods, Jupiter, was connected with the cult of the oak tree. The Arcadians thought that men were born from oak trees. On Mount Liceo, in Arcadia, the character of Zeus as god of the oak is evidenced by a ritual related to the rain by Frazer, who wanted the priest to immerse an oak branch in a sacred spring to ask the god for rain. In classical times, feasts in honor of Daedalus were celebrated, as Pliny tells us, in “forests of oaks” at whose feet pieces of meat were placed which then became food for the birds from which prophecies were taken out. Ixion, a Greek demigod, healed from ailments using the mistletoe grown on the oak. The name itself could come from daixias, or mistletoe. He was depicted as king of the oak with mistletoe genitals.

It is Virgil, in fact, who narrates that on the Campidoglio, the first temple dedicated to Romulus had been built near a sacred oak. It is the oldest Roman sanctuary dedicated to this divinity. During the Capitoline festivities associated with the god, the victor was adorned with a crown of oak leaves. This consecration must have had even more distant roots, probably according to Fazer the kings of Alba had to wear oak crowns so much so that this population was also called “men of oak”, probably because of the forests in which they lived. The Capitoline cult, therefore, must have been very ancient and derived from some autochthonous ritual of Mount Albano. Dodona, Herodotus tells of a cult centered around the oak sacred to Zeus, which involved the interpretation of the rustling of the leaves of the sacred tree. It is said that even Ulysses had gone to Dodona to hear the will of Zeus from the god’s lofty oak, and the same was true for Aeneas.

Therefore, Pliny probably connects the Druid-Priest to Mediterranean cults and associates him with the sacred tree par excellence: the Oak. Even the well-known writing by Pliny, in the NaturalisHistoria, which infers the importance of the oak would have at least one problem.

“The Druids held nothing more sacred than mistletoe and the tree on which it grows, provided it bears traits of a robur. They already choose the oak woods as sacred as such, and do not perform any religious rites if they do not have branches of this tree (…). they believe that everything that grows on oak trees is sent from heaven, a sign that the tree has been chosen by the deity himself. Furthermore, oak mistletoe is very rare to find and when it is discovered it is collected with great devotion: first of all on the sixth day of the moon (which marks the beginning of the month and year and century for them, every thirty years) and this because on that day the moon already has enough strength and is not at half. The name they gave to mistletoe means “that heals all”. After having prepared the sacrifice and the banquet according to the ritual at the foot of the tree, they bring two white bulls to which the horns have been tied for the first time. The priest, dressed in white, climbs the tree, cuts the mistletoe with a golden sickle and collects it in a white cloth. Then they immolate the victims, praying the god to make the gift (the mistletoe) favorable to those for whom they intended it. They believe that mistletoe, taken in potion, gives the ability to reproduce to any sterile animal, and that it is a remedy against all poisons”.

The Aryans and in particular the Celts were strongly linked to the oak but for what grew on it: the mistletoe. It was this plant, according to Frazer, that was the seed and germ of fire, an emanation of the sun god. It is legitimate to think that the golden splendor of the oak was the reflection of the marvelous golden branch.

So what could be the “true” Druidic sacred tree?

“…The birch, albeit very noble, only armed itself late, a sign not of cowardice but of high rank…”

According to Robert Graves, birch had particular sacredness. In the White Goddess the scholar highlights how it was this tree that opened the Celtic year in what is proposed as a sort of “Celtic calendar” even if it is difficult to verify. The tree is connected to solar rebirth, and therefore we find it, at least in Ireland, in the rituals associated with the Winter Solstice. Its sacredness is also manifested on Candlemas day and, at least in the Welsh tradition, on Beltane, given that it is this plant that provides the trunk for the May pole. Furthermore, the “king of the May” was completely covered with birch branches while the boys dressed up in hats made of birch bark and flowers.

The story in the Book of Ballymote says that Ogma son of Elathon, a manuscript datable to AD 600, states that Ogma carved the first Ogams into birch wood. It is also said that Ogma wanted to warn his brother Lugh of the danger that his wife was running of being taken to the Otherworld. So he carved seven Bs on a birch stick, meaning: “your wife will be taken seven times to the Underworld, or to some other world, unless she is protected by a birch”. Her sacredness could also be linked to the gift of vision and oracles. Under the fronds of him, tradition has it that the druids fell into a trance. This belief certainly has some truth to it. In fact, the Amanita Muscaria, consumed in many Nordic cultures precisely with the aim of entering a trance, preferably grows among the roots of this tree.

Yet other writers question the primacy of birch.

And if instead it was the Melo, the missing hero not for strength and courage but for “language”?

The poem Vita Merlini tells how the famous druid used to teach under this tree. Furthermore, in Breton mythology, before prophesying, one had to eat an apple, a fruit that made it possible to connect worlds. In the poems YrAfallennau and YrOianau the madness of the wizard Merlin is described who, in a forest, spoke to an apple tree. Madness or Vision? The Apple is the food that comes from the Underworld as demonstrated by the adventure of Condle, son of King Conn, who receives an apple from the Lady of the Other World that feeds him without ever being consumed. The apple is therefore an underworld tree that grows in Avalon, the mythical world where heroes rest.

Another important sacred tree is the Yew, as highlighted by Chetan and Brueton in the essay The SacredYew.

So after some evaluations, rather than a link between the Druid and the tree, it would perhaps be more correct to highlight a strong relationship between the Druid and the cult of Trees. For the Celts the forest has always been a sacred place, it was the nemeton or the drunemeton, the sacred grove. The Druidic temples were therefore among the a

Lascia un commento