di Andrea Romanazzi

Italian witchcraft cannot be separated from the amulet. There is a clear distinction between amulets, from the Latin amoliri, meaning “to ward off,” and talismans, from the Greek word telesma, meaning “consecrated object.”

The etymology itself marks the difference between the two types of magical protection. The amulet is inherently sacred, as nature infuses it with the particular virtues it possesses. The talisman, however, is created by man and endowed with specific properties by the Magician. It is thus an “evolved” object, artificially composed by someone with magical consciousness, often involving graphic elements and sometimes made from precious metals. Delving into the history of talismanic practices would be too broad, as it is a magical form originating far from the popular world I have chosen to investigate here. Much more interesting is to focus on the traditional amulets prevalent in folk medicine and belief. In our exploration of magical folk traditions, we have already encountered these objects with strange and divine virtues.

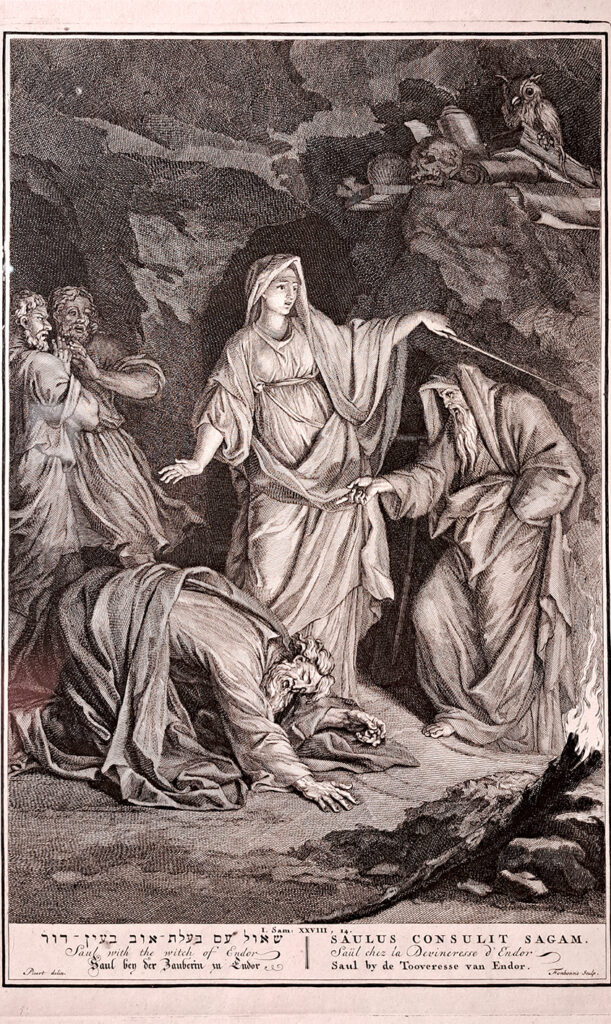

The idea of the supernatural power of the amulet has its roots in the primordial religion of the Ancients: fetishism. This term likely derives from the word “fetish,” used by the first Portuguese explorers to designate the magical or enchanted objects of tribal populations, which were believed to possess particular powers and the ability to influence not only the lives of animals and humans but also emotions and passions. In reality, two types of fetishism can be distinguished: “primitive” and “derived.” For the Ancients, this phenomenon was the only form of religious expression, and the fetish itself represented a sacred entity, being the incarnation of a specific deity, created by the will of the fetishist, worshipped by one or a few, and independent of any other deity represented by other fetishes. The devotee was thus the priest of himself and the creator of his fetish. This could be abandoned and replaced by another when it no longer met the owner’s expectations and desires, without concern for its fate. In derived fetishism, or the fetishism that develops in what we might call “evolved religions” for clarity, fetishes are only partial and secondary manifestations of the superior entity worshipped. Thus, unlike primitive fetishism, the main deity can simultaneously be present in multiple related fetishes. These can be worshipped by a large number of people who, unlike the ancient faithful, are subject to a hierarchy of priests. Unlike primitive fetishism, the faithful may abandon the fetish in which they no longer trust but will never abandon their god. Therefore, while the first form of fetishism is individual and at most familial, the second is a more complex form of collective worship. When humans begin to imagine a “disembodied” entity, not bound by matter but capable of existing outside of it, the transition from fetishism to totemism occurs. With the advent of Christianity, the use of amulets was forbidden but never eradicated. Pope Martin I, in the First Lateran Council of 649, condemned the use of such objects, a condemnation that went unheeded. Martin del Rio, in his “Magical Disquisitions,” described and condemned their use. In reality, amulets still constitute an essential element of popular magic and witchcraft today.

Types of Amulets

It is not easy to give a precise classification of amulets. A first and simplistic division could be related to their effectiveness and attributed virtues.

We could thus divide amulets into four classes or groups:

- Amulets meant to prevent or ward off the manifestation of particular natural phenomena and to protect people, things, or animals.

- Amulets with preventive and curative properties for certain diseases.

- Protective amulets against evil spells cast by witches, demons, or other malevolent entities.

- Amulets used to promote and bring good fortune in general.

In reality, many other “classifications” could be made, for example, depending on whether their virtues are naturally acquired or later infused through rituals. In this way, the second category would include all those objects that are not naturally amulets but became so through contact with other sacred objects, acquiring the same virtues. Amulets also include objects inspired by religious concepts, such as effigies and medals of particular saints, for example, the medal of St. Donatus, as well as Christian relics ex ossibus, derived from the bones of sacred figures, or those associated with the saints’ vestments, classified respectively as first and second class. According to Christian rites, objects that come into contact with first- or second-class relics become third-class relics. Often, the power of the amulet stems from the magical principles of “like attracts like” or “opposites,” such as the hanged man’s rope, skulls, or the number 13. Primarily, however, their power falls into well-defined magical classes. An example is the “magic of points,” which includes many amulets like the Neapolitan horn, scissors, nails, or hands making the horn gesture. What unites these objects is the “point,” which becomes a tool of defense while also being a remnant of the much older magic of the nail, which deserves a deeper exploration. Many amulets take the form of animals, such as frogs, lizards, and fish, often linked to the concept of similia similibus or the use of the harmful agent to repel itself. Hence the representation of animals often associated with witches’ magical abilities. A particular amulet is the “toad stone” or lapis bufonis, small smooth pebbles gathered from ponds heavily populated by toads. Somewhere between the two types described are animal organs, particularly claws and teeth, which relate to both point magic and animal power. In Rome, it was customary to place a wolf’s tooth on doorways, and in Abruzzo, dog teeth were used to protect against rabid animal bites. The magic of metals is another important aspect of amulet-making. Amulets were often made of gold, endowed with particular healing and prophylactic virtues, while lead was used for intestinal diseases. The “horseshoe” embodies all the prophylactic types described. This amulet resembles the “crown of imposition,” evoking the concept of like attracting like, is made of iron, a material that “draws negativity,” and is linked to an animal revered for its utility. The same applies to the key, an amulet useful against the evil eye and used to cure epilepsy. In Abruzzo, “magic” keys were forged from ancient, disused bells on Holy Saturday. The magic of counting includes amulets like badger hair tufts, sacks of grain, brooms, and iron residues. Tradition holds that witches had to count before entering a house or casting their spells, and not knowing how to do so, they would lose all the nighttime hours available to them. Herbs also play a role in amuletic purposes, such as rue, considered by the Romans a protector against witchcraft and spells. A brief mention of the “Cimaruta” is an amulet made of a rue branch with various apotropaic charms at its ends. The author Robert Theodore Gunther published a long article in the 1905 “Folklore Quarterly Review” discussing the Cimaruta as a pagan Italian amulet, linking it to Diana. The topic was later revisited by Doreen Valiente in “ABC of Witchcraft” and by Raven Grimassi in his book “The Cimaruta: And Other Magical Charms From Old Italy,” where he discusses the charm as a sign of membership in the “Society of Diana,” referring to it as an organization of witches. Olive leaves, potentilla leaves, also known as five-finger grass, and hanging tree herbs are essential elements of the “brevi,” bags made of various colored fabrics, often heart-shaped or triangular, containing religious or amuletic objects that had to be worn at all times. Many amulets are also associated with the color “red,” a protective color against the evil eye and witchcraft since the time of Aristophanes, who mentions it in his “Plutus.” The reference is likely to blood, the source of life, particularly menstrual blood. Examples include ribbons, bows, bracelets, and horns. The prophylactic magic of sound is found in bells, which actually encompass multiple meanings, from the metal to the sexual symbolism of the vulva and clapper, representing the union of the male and female elements. Their sound is believed to ward off negativity and evil spirits.

This overview clearly illustrates the different cases of traditional Italian amulets. An alternative way to differentiate a specific type of amulet is by observing distinctive features in some objects that are not normally found in nature. Think, for example, of the four-leaf clover or the trilobate walnut shell. To the ancient eye, the anomaly was not random but a sign of something “monstrous” in the Latin sense of the term. They believed these objects could ensure good fortune. Even in the case of “Christian amulets,” as we have previously mentioned, fragments of pagan superstitions absorbed by Christianity through a syncretic operation are evident, as they were too difficult to eradicate from the rural mindset.

Lascia un commento