di Andrea Romanazzi

Il ricorso alla stregoneria, e in particolare agli oggetti malefici, è un fenomeno che attraversa trasversalmente culture e periodi storici, ma che in Europa assume un particolare significato sociale e culturale.

Come testimoniano oggetti presenti in molti museo popolari, esistono vari artefatti che non sono solo testimoni di superstizioni locali, ma diventano potenti simboli di ansie collettive e di sofferenze individuali. La loro capacità di influenzare le vite di coloro che li creano, possiedono o subiscono è ancorata in profondi strati di credenze e pratiche magico-religiose che cercano di dare un senso all’inspiegabile.

La figura del malheureux sorcier

Il “malheur sorcier”, o “sfortuna del mago”, è un concetto che emerge dalla convinzione che eventi negativi, come malattie o fallimenti, possano essere il risultato di malefici voluti da individui con presunti poteri magici. Nella cultura contadina, soprattutto nelle regioni rurali, il sospetto di stregoneria nasce spesso in risposta a disgrazie improvvise: la morte del bestiame, la distruzione dei raccolti, o malattie misteriose.

Gli oggetti malefici: il simbolismo della distruzione

In passato, camminando in campagna, non era raro imbattersi in bambole di paglia, trapassate da chiodi o altre figure umanoidi, che erano usate per trasmettere malattie o dolore a una vittima designata, nella convinzione che il danno ad essi inflitto si potesse riverberare fisicamente sulla persona bersagliata.

Il malheur sorcier nella vita quotidiana

Come descritto nelle testimonianze riportate, il “malheur sorcier” entrava spesso nella vita quotidiana sotto forma di disastri apparentemente casuali. Una vacca che abortisce misteriosamente, un contadino che si ammala senza spiegazione, o un’intera famiglia afflitta da malesseri inspiegabili, potevano essere causati sospetto che tali eventi dagli “hommes du don” (uomini dotati di poteri).

La Stregoneria in Italia: Un Affare Popolare

Quando si pensa alla stregoneria in Italia, non bisogna immaginare solamente le scene cruente dei roghi che si sono consumati in altri paesi europei durante il Medioevo e l’Inquisizione. La stregoneria italiana, pur avendo subito l’influenza di questi eventi, si è sviluppata in maniera peculiare, rimanendo ancorata principalmente alla sfera della vita quotidiana. Il termine “strega” in Italia ha un significato duplice. Da un lato, indica la persona in grado di infliggere danni attraverso l’uso di pratiche occulte, dall’altro, è anche la figura che cura, che guarisce e che protegge la comunità da mali invisibili. Nelle regioni rurali, in particolare nel sud Italia e nelle aree appenniniche, la figura della strega o del mago era quella di un personaggio rispettato e temuto allo stesso tempo. Questi “uomini e donne di potere” non erano individui reietti, bensì parte integrante del tessuto sociale. Venivano consultati per problemi quotidiani come la malattia del bestiame, la protezione dei raccolti, l’amore e la fertilità. La loro capacità di entrare in contatto con forze invisibili, a volte considerate naturali, altre soprannaturali, li rendeva un punto di riferimento per chi non trovava risposte altrove.

Gli Amuleti e le Protezioni: Un’Arte di Resistenza

Uno degli aspetti centrali delle pratiche magiche italiane è la realizzazione di oggetti che possano fungere da protezione contro i mali, le sfortune o le influenze negative. Gli amuleti non erano soltanto simboli religiosi o decorativi, ma veri e propri oggetti carichi di potere, realizzati attraverso rituali specifici. Le mani, la cera, i capelli o persino le ossa potevano essere utilizzati per costruirli amuleti e erano testimoni usati a scopi diversi: protezione, vendetta, guarigione o fertilità. In molte tradizioni locali, il processo di creazione di questi amuleti era avvolto nel mistero, e solo chi possedeva determinate conoscenze esoteriche poteva confezionarli correttamente.

In alcune zone d’Italia, ad esempio, si credeva che determinati oggetti potessero incanalare le energie spirituali in maniera tale da influenzare il corso della vita di una persona. Questi oggetti, spesso associati a riti segreti, venivano usati anche per proteggere le case, i campi e gli animali. Era comune, nelle aree rurali, nascondere amuleti nei muri o nei pavimenti delle abitazioni come forma di protezione contro la sfortuna o le influenze maligne. Anche i neonati venivano spesso protetti con simboli e oggetti benedetti, che venivano appesi sopra le loro culle per difenderli dagli influssi negativi del mondo.

Il Malocchio e le Sue Cure

Tra le credenze più diffuse in Italia, vi è quella del malocchio. Il concetto di malocchio è antichissimo e ha radici che affondano nel Mediterraneo pre-cristiano. Ancora oggi, in molte parti d’Italia, il malocchio è visto come una delle principali fonti di sfortuna, malattia e disgrazie. Si crede che possa essere inflitto involontariamente o, in alcuni casi, con intento malevolo. Colui che subisce il malocchio sperimenta sintomi quali mal di testa, spossatezza, malessere generale e, nei casi più gravi, si pensa che possa provocare incidenti o malattie.

Per rimediare al malocchio, esistono diversi rituali che variano a seconda delle regioni. In generale, il rituale del “segreto” è uno dei più comuni. Esso consiste nel recitare una preghiera o una formula segreta (spesso tramandata oralmente e conosciuta solo da pochi eletti) mentre si osservano determinati segni, come l’andamento dell’olio versato in acqua o il movimento del piombo fuso nell’acqua fredda. Se l’olio si separa in piccole gocce, o se il piombo assume una forma irregolare, allora si ritiene che la persona sia effettivamente vittima di malocchio, e il rito prosegue con formule magiche o preghiere di purificazione.

In alcune regioni del Sud, la diagnosi di malocchio è legato anche all’uso di elementi naturali come il sale e l’acqua. Il sale, ad esempio, viene spesso sparso intorno alla casa o alla persona afflitta per allontanare le energie negative. In altri casi, l’acqua benedetta viene utilizzata per ungere la fronte della persona colpita dal malocchio, accompagnata da una preghiera o da un gesto simbolico, come il segno della croce.

Il Ruolo del Guaritore e della Guaritrice

Nelle comunità rurali italiane, fino al XIX e XX secolo, era comune rivolgersi a figure di guaritori locali, che spesso esercitavano una sorta di medicina popolare parallela a quella ufficiale. Queste persone, conosciute con vari nomi a seconda delle regioni (come “maghi”, “fattucchieri”, “ciarlatani” o “guaritrici”), erano coloro che possedevano il sapere antico e spesso esoterico delle erbe, dei rimedi naturali e delle preghiere di guarigione. La figura della guaritrice, in particolare, era estremamente importante per la comunità. Queste donne, spesso considerate streghe o maghe, avevano un ruolo ambivalente: da una parte erano coloro che guarivano le malattie e difendevano dal malocchio; dall’altra, la loro conoscenza delle erbe e dei rituali le rendeva temute e rispettate. Il loro potere risiedeva in una profonda conoscenza delle proprietà curative delle piante, ma anche nella capacità di entrare in contatto con il mondo spirituale per ottenere informazioni e poteri sovrannaturali.

La guaritrice preparava pozioni, unguenti e decotti a base di piante locali, che venivano utilizzati per trattare una vasta gamma di disturbi. Questi rimedi non erano considerati solo soluzioni fisiche, ma avevano anche un valore spirituale e simbolico. Si credeva che, attraverso il potere delle parole e delle preghiere, la guaritrice potesse riequilibrare le energie interne ed esterne della persona malata, aiutandola a ristabilire l’armonia con la natura e con se stessa.

Le Maledizioni e la Stregoneria Nera

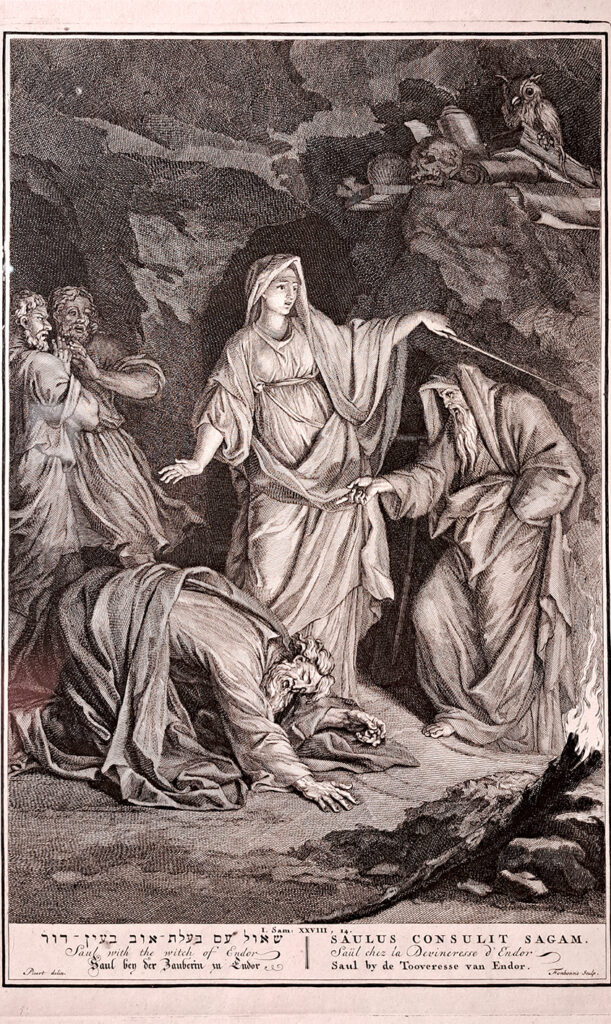

Oltre alla magia “bianca”, utilizzata per la protezione e la guarigione, esisteva anche la credenza nella magia “nera”, o stregoneria maligna. Questa forma di stregoneria era temuta, poiché implicava l’uso di poteri occulti per nuocere intenzionalmente a qualcuno. Le maledizioni erano uno degli strumenti principali di questa pratica, e si riteneva che fossero in grado di provocare malattie, morte, sfortuna o rovine economiche.

Venivano spesso realizzate con rituali complessi, che includevano l’uso di oggetti personali della vittima, come capelli o pezzi di vestiti, incantati attraverso formule magiche. Un altro metodo comune era quello di seppellire determinati oggetti simbolici (come bambole di cera o animali morti) vicino alla casa o alla proprietà della persona da maledire, in modo che la maledizione potesse agire direttamente sull’ambiente della vittima.

La Sopravvivenza della Magia nelle Tradizioni Moderne

Anche se il mondo moderno ha ridotto l’importanza delle credenze magiche nella vita quotidiana, esse continuano a sopravvivere in molte forme. Il folklore magico italiano rappresenta quindi un patrimonio culturale che continua a influenzare la vita delle persone, anche in modi sottili e spesso inconsci. La magia, come forma di resistenza contro le forze sconosciute della vita, rappresenta un elemento chiave della cultura italiana, un simbolo del potere dell’immaginazione e della speranza di poter influenzare, in qualche modo, il proprio destino.

——–

The resort to witchcraft, particularly the use of malevolent objects, is a phenomenon that transcends cultures and historical periods, but in Europe, it takes on a unique social and cultural significance.

As evidenced by objects in many folk museums, there are various artifacts that are not merely remnants of local superstitions but become powerful symbols of collective anxieties and individual suffering. Their ability to influence the lives of those who create, own, or are affected by them is anchored in deep layers of magical-religious beliefs that seek to make sense of the inexplicable.

The Figure of the Malheureux Sorcier

The “malheur sorcier,” or “the sorcerer’s misfortune,” emerges from the belief that negative events such as illness or failure could be the result of curses cast by individuals with supposed magical powers. In rural culture, particularly in agricultural regions, suspicion of witchcraft often arose in response to sudden misfortunes: the death of livestock, the destruction of crops, or mysterious illnesses.

Malevolent Objects: The Symbolism of Destruction

The malevolent objects, often charged with symbolic power, were believed to cause harm to the intended target. For instance, the feathered heart not only represents a metaphor for the human heart, fragile and vulnerable, but also a means of inflicting suffering. Feathers, sewn together in a heart shape, symbolized broken familial or romantic ties, often the result of jealousy or personal vendettas. In the past, it was not uncommon to find straw dolls impaled with nails or other humanoid figures, used to transmit disease or pain to a designated victim. The belief was that the harm inflicted on the doll would physically manifest in the person targeted.

The Malheur Sorcier in Everyday Life

As described in various testimonies, the malheur sorcier often manifested in daily life as seemingly random disasters. A cow that mysteriously miscarried, a farmer who fell ill without explanation, or an entire family stricken by unexplained ailments were often seen as victims of witchcraft. In such cases, people sought the help of local healers or “hommes du don” (men with the gift), hoping to break the curse and restore balance.

Witchcraft in Italy: A Popular Affair

When thinking of witchcraft in Italy, one must not imagine only the brutal scenes of burnings that took place in other European countries during the Middle Ages and the Inquisition. Italian witchcraft, while influenced by these events, developed in a peculiar way, remaining primarily anchored in daily life. In Italy, the term “witch” carries a dual meaning. On one hand, it refers to someone capable of inflicting harm through occult practices; on the other, it also designates the figure who heals, protects, and safeguards the community from unseen evils. In rural regions, particularly in Southern Italy and the Apennine areas, the figure of the witch or the mage was both respected and feared. These “men and women of power” were not outcasts, but integral members of the community, consulted for issues such as livestock illness, crop protection, love, and fertility. Their ability to interact with invisible forces, sometimes considered natural and at other times supernatural, made them essential points of reference for those seeking answers.

Amulets and Protections: An Art of Resistance

One of the central aspects of Italian magical practices is the creation of objects that serve as protection against evil, misfortune, or negative influences. The most famous of these objects is undoubtedly the “corno” (horn), a symbol of protection against the evil eye, still widely used in Southern Italy today. The evil eye, or “jettatura,” is the belief that a malevolent gaze can bring bad luck or illness. Amulets were (and still are) carried as protection against this.

Amulets were not merely religious or decorative symbols; they were charged with power, created through specific rituals. Hands, wax, hair, and even bones could be used to construct amulets for various purposes: protection, revenge, healing, or fertility. In many local traditions, the process of creating these amulets was shrouded in mystery, and only those with certain esoteric knowledge could craft them correctly.

In some regions of Italy, it was believed that certain objects could channel spiritual energies to influence the course of someone’s life. These objects, often associated with secret rites, were also used to protect homes, fields, and animals. It was common in rural areas to hide amulets in the walls or floors of houses as protection against misfortune or evil influences. Even newborns were often protected with blessed symbols and objects hung over their cradles to shield them from the negative forces of the world.

The Evil Eye and Its Remedies

One of the most widespread beliefs in Italy is that of the evil eye. The concept of the evil eye is ancient, with roots in the pre-Christian Mediterranean. Even today, in many parts of Italy, the evil eye is seen as one of the primary causes of bad luck, illness, and misfortune. It is believed that the evil eye can be cast unintentionally or, in some cases, with malevolent intent. Victims of the evil eye experience symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, general malaise, and in more severe cases, it is thought to cause accidents or illness.

To remedy the evil eye, there are various rituals that differ depending on the region. In general, the ritual of the “segreto” (secret) is one of the most common. It consists of reciting a secret prayer or formula (often passed down orally and known only by a select few) while observing specific signs, such as the movement of oil dropped in water or the shape of molten lead when poured into cold water. If the oil forms small droplets or the lead takes on an irregular shape, it is believed that the person has been afflicted by the evil eye, and the ritual continues with magical formulas or prayers for purification.

In some southern regions, the evil eye is linked to the use of natural elements such as salt and water. Salt, for instance, is often scattered around the house or the afflicted person to ward off negative energies. In other cases, blessed water is used to anoint the forehead of the person affected by the evil eye, accompanied by a prayer or symbolic gesture, such as the sign of the cross.

The Role of the Healer and the Witch

In rural Italian communities, up until the 19th and 20th centuries, it was common to turn to local healers who often practiced a form of folk medicine parallel to the official one. These individuals, known by various names depending on the region (such as “maghi,” “fattucchieri,” “ciarlatani,” or “guaritrici”), were those who possessed ancient, often esoteric knowledge of herbs, natural remedies, and healing prayers.

The figure of the healer, particularly women, played an essential role in the community. These women, often considered witches or mages, held an ambivalent position: they were the ones who healed the sick and defended against the evil eye, but their knowledge of herbs and rituals also made them feared and respected. Their power lay in their profound knowledge of the healing properties of plants, but also in their ability to communicate with the spiritual world to gain information and supernatural powers.

The healer prepared potions, ointments, and decoctions using local plants, which were used to treat a wide range of ailments. These remedies were not just seen as physical solutions but also carried spiritual and symbolic value. It was believed that through the power of words and prayers, the healer could restore balance to the internal and external energies of the sick person, helping them to regain harmony with nature and themselves.

Curses and Black Magic

Alongside “white” magic, used for protection and healing, Italy also harbored a belief in “black” magic, or malevolent witchcraft. This form of witchcraft was feared as it involved using occult powers to harm others intentionally. Curses were a primary tool of this practice, believed to cause illness, death, misfortune, or financial ruin.

Curses were often performed through complex rituals that included the use of the victim’s personal belongings, such as hair or clothing, which were enchanted through magical formulas. Another common method was to bury symbolic objects (such as wax dolls or dead animals) near the home or property of the cursed person, with the belief that the curse would act directly upon the victim’s environment.

Binding love spells were also common among those who sought control over another person. It was believed that through specific rituals and the use of symbolic objects, one could influence the behavior and feelings of another, binding them indissolubly. These rituals were often commissioned by jealous or enamored individuals willing to do anything to win the heart of their desired partner.

The Survival of Magic in Modern Traditions

Although modern life has diminished the importance of magical beliefs in everyday life, they continue to survive in many forms. Beliefs in the evil eye, love spells, and white magic are still widespread, especially in rural communities and among older generations. However, these practices have also found new life among younger people who see them as a way to reconnect with their cultural roots.

Italian magical folklore remains a cultural heritage that continues to influence people’s lives, often in subtle and unconscious ways. Magic, as a form of resistance against the unknown forces of life, represents a key element of Italian culture, a symbol of the power of imagination and the hope that one can, in some way, influence their own destiny.

Lascia un commento